Disclaimer: This article provides a qualitative overview of hiring trends based on publicly available labour market statistics, economic forecasts, and institutional analysis. It is intended to support understanding and workforce planning rather than formal forecasting or statistical prediction. This assessment reflects conditions and projections as of late 2025; labour market outcomes may vary by region and evolve with economic or policy changes. A labour market characterised by tightness, migration dependency, and moderate corporate contraction

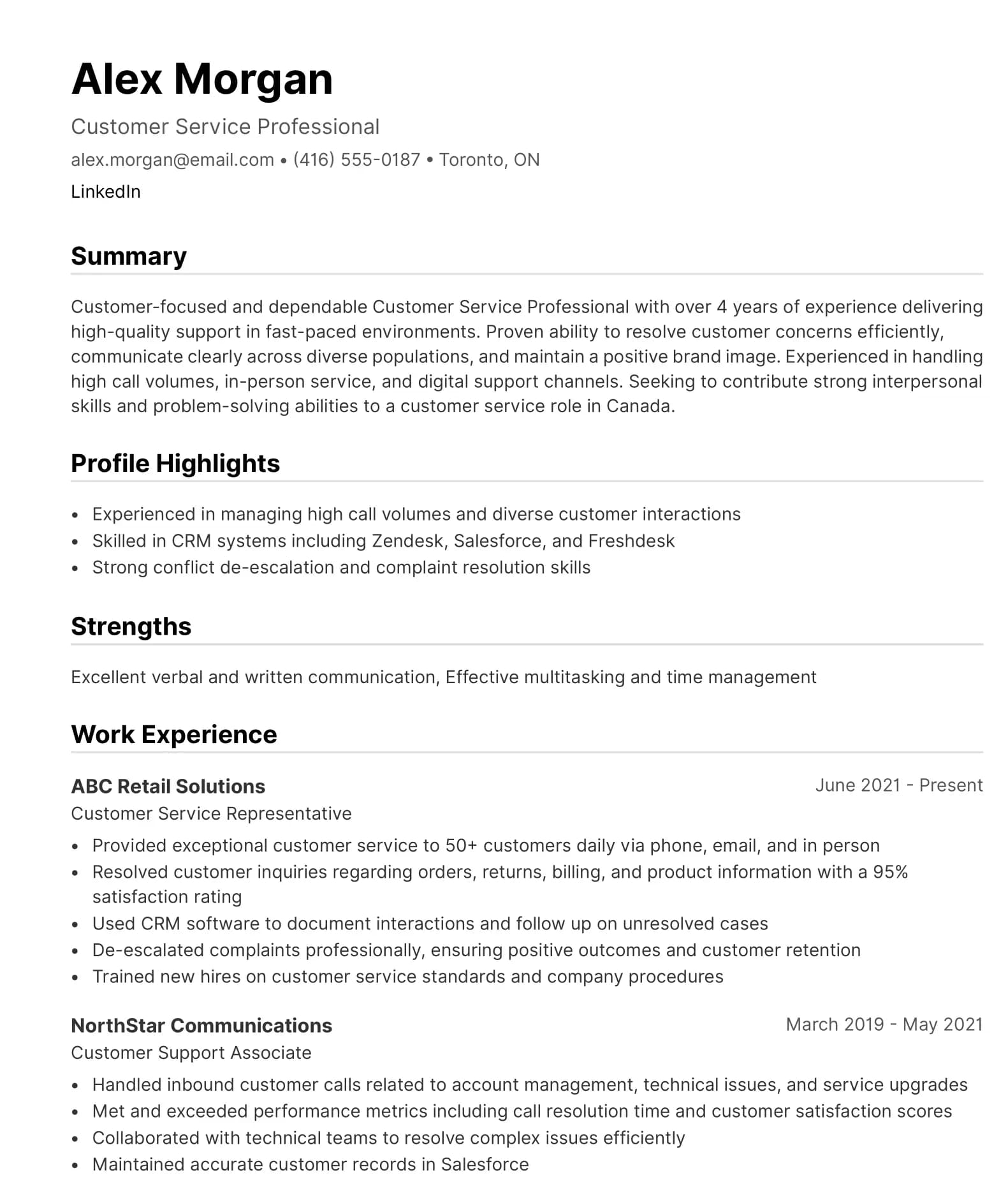

ATS-Optimized resumes That Meet Employer Standards

Our AI-powered scoring system helps organizations assess and standardize resume quality at scale. ATS-compliant templates support consistent formatting, keyword alignment, and interview readiness across cohorts.

Poland's labour market in 2026 reflects a complex picture: sustained low unemployment coexisting with critical labour shortages, modest wage growth against inflationary pressures, and increasing reliance on foreign workers to fill positions domestic workers increasingly reject or emigrate from.

Over 17.8 million people participate in Poland's labour market, with an employment rate of around 72% for working-age adults (15-64), approximately two percentage points above the EU average. This represents substantial improvement from earlier periods, with employment rates having increased by roughly five percentage points since 2018.

However, unemployment remains exceptionally low at around 3-4% according to harmonised measures (with domestic registered unemployment somewhat higher at around 5-6%), creating a tight labour market where employers struggle to fill positions. The job vacancy rate stands at approximately 0.8-0.9% in industry, construction, and services, below the EU average but higher than the early-2010s lows and only slightly below the 2022 peak of around 1.3%, indicating persistent unfilled demand.

A notable development affecting the 2026 market is corporate employment contraction. Recent data shows corporate sector employment (enterprises with over nine employees) has declined for around two years consecutively, with year-on-year decreases of approximately 0.8-0.9% through mid-2025. This corporate adjustment coexists paradoxically with overall labour shortages, reflecting restructuring, automation, and sectoral shifts.

Average monthly wages stand at approximately PLN 8,700-8,800 (around USD 2,200-2,300 or EUR 2,000-2,100) according to recent reporting, with central bank scenarios suggesting more modest wage growth in 2026-2027 (around 5-6% annually) compared to the substantial increases seen in 2024 (approximately 13-14%). The minimum wage increased to PLN 4,666 monthly (approximately USD 1,200) as of January 2025, reflecting Poland's commitment to raising living standards.

This analysis is most relevant to employers, HR professionals, job seekers, training providers, policymakers, and institutions supporting workforce development in Poland's tight but evolving labour market.

1. Foreign workers increasingly essential to labour market function

Poland's labour market has become fundamentally dependent on foreign workers, with over one million foreign citizens now legally working in the country according to official statistics. This represents a transformation from supplemental to structural reliance, with some industries unable to operate without migrant labour.

Ukrainian workers dominate: Ukrainian citizens represent the largest foreign worker group, numbering in the hundreds of thousands. Geographic proximity, cultural similarities, low language barriers, and Poland's support following Russia's 2022 invasion have made Poland a primary destination. Many positions in logistics, manufacturing, construction, and hospitality are now substantially filled by Ukrainian workers.

Asian migration growing: Workers from India, Bangladesh, the Philippines, Nepal, and other Asian countries increasingly fill positions, particularly in logistics, manufacturing, and services. Work permit issuances for foreigners increased several-fold (well over three times) between 2015 and 2023, reflecting accelerating foreign worker recruitment.

Sectors heavily dependent on foreign labour:

- Logistics and warehousing: Poland's position as a European logistics hub creates massive demand; foreign workers now essential for warehouse operations, sorting, packaging, and distribution

- Manufacturing: Food production, plastics, electronics, automotive parts, and other manufacturing face continuous workforce needs; younger Polish citizens increasingly seek opportunities abroad, leaving production roles to migrants

- Construction: Infrastructure projects, housing development, and renovation work face persistent labour shortages; ageing domestic workforce and insufficient skilled workers among locals drive foreign recruitment

- Hospitality: Hotels, restaurants, and food services (especially in tourist cities like Warsaw, Kraków, Wrocław) actively employ migrants to maintain operations

Implications of migration dependency: This structural reliance creates vulnerabilities (geopolitical disruptions, policy changes, or economic conditions in source countries directly affect Poland's labour supply) but also opportunities (foreign workers enable economic activity that would otherwise be constrained by domestic labour availability).

So what

For candidates: Foreign workers find abundant opportunities in Poland, particularly in logistics, manufacturing, construction, and hospitality; language barriers less prohibitive than in many European countries due to large foreign worker communities and employer adaptation.

For employers: International recruitment is no longer optional but essential for many sectors; investing in foreign worker support (housing, integration, language assistance) improves retention and productivity.

2. Critical skill shortages persist in trades, technical roles, and healthcare

Despite low unemployment, Poland faces severe shortages in specific occupational groups. According to labour market analyses, building and related trades workers (excluding electricians), metal and machinery trades workers, and teaching professionals represent the occupational categories with highest shortage occurrence in 2024.

Skilled trades: Construction workers, welders, electricians, plumbers, HVAC technicians, and machinery operators face persistent recruitment challenges. Recent data indicates tens of thousands of unfilled positions in construction, manufacturing, and related technical trades. An ageing domestic workforce, insufficient vocational training, and young workers' preference for office-based or foreign employment exacerbate shortages.

Healthcare professionals: Nurses, doctors, psychologists, and psychotherapists face substantial shortages. While not as severe as in some Nordic countries, healthcare workforce gaps create service delivery challenges, particularly outside major cities. Emigration of healthcare professionals to Western Europe compounds domestic shortages.

IT and technology: Software developers, cybersecurity specialists, data analysts, and IT project managers remain in high demand. Poland's growing technology sector (both domestic companies and international firms establishing operations) creates sustained competition for technical talent. IT professionals with experience often earn in the PLN 9,000-12,000 monthly range or higher in major hubs (approximately USD 2,300-3,100), making technology among Poland's highest-paying sectors.

Teachers: Educational workforce shortages persist, particularly in STEM subjects and vocational training. Teacher compensation remains modest relative to private sector alternatives, creating retention challenges.

Drivers: Truck drivers face particular shortage, with logistics sector expansion creating sustained demand that exceeds domestic supply. Foreign drivers increasingly fill these roles.

These shortages are structural rather than cyclical, driven by demographic decline (working-age population projected to decrease by approximately two million by 2040), emigration of skilled workers to higher-wage Western European labour markets, and insufficient training pipelines in critical technical fields.

So what

For candidates: Skills in trades, healthcare, IT, and technical fields provide exceptional employment security and negotiating leverage; certifications and practical experience highly valued.

For employers: Shortage occupation recruitment requires competitive compensation, clear advancement paths, and willingness to train or credential-recognize adjacent talent; foreign recruitment increasingly necessary.

3.Wage growth moderating after substantial 2024 increases

Poland experienced substantial wage growth in 2024, with salaries rising by approximately 13–14% year-on-year. This acceleration was driven by inflationary pressures, acute labour market tightness, and repeated minimum wage increases. However, central bank projections and employer planning data indicate a clear slowdown. Wage growth is expected to moderate to around 5–6% annually in 2026–2027, potentially easing further toward 5% by 2027 as inflation stabilises and companies prioritise cost control.

Average Salary in Poland (2026 Snapshot)

Headline figures

- Average gross monthly salary: PLN 8,735–8,771 (approximately USD 2,100–2,200 or EUR 1,950–2,050, depending on exchange rates)

- Median monthly salary: PLN 6,540–6,641 (approximately USD 1,650–1,710)

- Minimum wage (January 2025): PLN 4,666 per month or PLN 30.50 per hour

Salary distribution

- Lower-end earnings cluster around PLN 4,000 per month

- Higher-end professional and specialist roles commonly reach PLN 12,000 per month or more

The substantial gap between average and median pay indicates meaningful wage inequality. Roughly half of Polish workers earn below PLN 6,640 per month, despite headline wage figures suggesting higher average earnings.

Net pay reality

A gross salary of approximately PLN 8,750 translates into a net monthly income of around PLN 6,290 after income tax and social security contributions. This gap between gross and take-home pay materially affects household purchasing power and wage expectations.

Structural wage patterns and differences

Average monthly gross wages in the enterprise sector stand at approximately PLN 8,700–8,900 as of late 2025. While wages continue to grow, the pace is now significantly slower than during the inflation-driven surge of 2024.

Poland exhibits relatively high earnings inequality compared to most EU countries. The top 10% of earners receive roughly four times the income of the bottom 10%, reflecting a right-skewed wage distribution driven by high-paying professional and technical roles.

Sectoral differences are pronounced. Information and communication, technology, finance, and healthcare offer the highest median wages, often exceeding PLN 10,000–11,000 per month. In contrast, hospitality, cleaning, and basic services remain among the lowest-paid sectors. Manufacturing and construction wages tend to cluster around national averages, with variation based on skill level and specialisation.

Regional disparities further shape wage outcomes. Major cities such as Warsaw, Kraków, Wrocław, and Gdańsk typically offer salaries 20–30% higher than smaller cities and rural areas, though higher housing and living costs offset part of this premium.

Experience and education continue to deliver strong pay advantages. Employees with two to five years of experience earn approximately 30–35% more than entry-level workers, while holders of master’s degrees earn roughly 25–30% more than bachelor’s degree holders in comparable roles. Senior professionals with 15 or more years of experience command substantial additional premiums.

Poland maintains one of the smallest gender pay gaps in the European Union, estimated at around 7–8%. Nonetheless, disparities persist at senior levels and within specific industries.

So what

For candidates: Wage growth expectations should adjust downward from the exceptional levels seen in 2024. Strong negotiation outcomes increasingly depend on experience, scarce skills, and alignment with shortage occupations rather than broad market inflation.

For employers: While overall wage pressure is easing, competition for talent in shortage roles remains intense. Employers are increasingly differentiating through non-wage benefits, career development opportunities, flexibility, and clearer advancement pathways as direct salary competition moderates.

4. Demographic decline creates long-term labour supply challenges

Poland faces substantial demographic headwinds that will intensify through 2030-2040. The working-age population is projected to decrease by approximately two million people by 2040 according to Statistics Poland, with this decline accelerating over time.

Ageing workforce: Poland's workforce ages rapidly, with large cohorts approaching retirement across sectors. This creates massive replacement demand independent of economic growth. The number of working pensioners has increased substantially (from approximately 575,000 in 2015 to around 850,000 as of 2023 according to Social Insurance Institution data), partly addressing labour shortages but creating succession planning challenges.

Low birth rates: Poland's birth rate remains below replacement level, meaning natural population decline continues. Without immigration, workforce contraction accelerates substantially.

Youth emigration: Young, educated Poles increasingly pursue opportunities in Western Europe, attracted by higher salaries (often 2-3 times Polish levels), better working conditions, and career development prospects. This "brain drain" particularly affects skilled technical fields, healthcare, and professional services.

Retirement age considerations: Poland's 2017 reversal of previous retirement age increases (returning to age 60 for women, 65 for men from the previously planned 67 for both) exacerbates demographic pressures. Earlier retirement reduces workforce participation precisely when demographic decline intensifies labour shortages.

Groups with lower participation: Women (particularly in the 20-24 age group due to education continuation and 60-64 age group due to retirement), people with disabilities, and some rural populations show lower labour force participation than EU averages, representing potential pools for increased engagement.

So what

For candidates: Demographic decline creates sustained long-term opportunities across all sectors; replacement demand ensures job security independent of economic cycles.

For employers: Workforce planning must account for retirement waves; retention, knowledge transfer, and succession planning become strategic imperatives; immigration recruitment increasingly essential.

For policymakers: Addressing demographic decline requires policy interventions around retirement age, labour force participation of underutilised groups, and immigration frameworks.

5. Corporate sector adjusting despite overall labour market tightness

A distinctive feature of Poland's 2026 labour market is corporate employment contraction despite overall low unemployment and labour shortages. Corporate sector employment (enterprises with more than nine employees) has declined consecutively for over two years, with year-on-year decreases of around 0.8-0.9% through mid-2025.

Factors driving corporate adjustment:

- Automation and productivity improvements: Companies invest in automation to address labour shortages and rising wage costs

- Restructuring and efficiency gains: Economic uncertainty drives operational streamlining

- Sectoral shifts: Decline in some traditional manufacturing segments; growth in services not always captured in corporate employment statistics

- Small enterprise and self-employment growth: Economic activity increasingly occurs outside large corporate structures counted in headline employment statistics

Coexistence with labour shortages: This corporate contraction coexists with severe shortages in specific roles, reflecting mismatch rather than surplus. Companies reduce headcount in some functions while struggling to fill others.

Wage growth despite employment decline: Interestingly, average wages continue growing despite falling corporate employment, suggesting companies retain higher-skilled, higher-paid workers while reducing lower-skilled positions through automation or outsourcing.

So what

For candidates: Corporate employment trends vary substantially by sector and skill level; shortage occupation positioning provides security even amid overall corporate adjustment.

For employers: Efficiency gains and productivity improvements become imperative amid labour scarcity and wage pressures; investment in automation and process improvement addresses shortages strategically.

6. Regional disparities create geographic labour market segmentation

Poland's labour market conditions vary substantially by region, reflecting economic structure, population distribution, and proximity to major economic centres.

Major cities and metropolitan areas: Warsaw, Kraków, Wrocław, Gdańsk, and Poznań concentrate professional services, technology, finance, and international business. These cities show higher employment rates, lower unemployment, substantially higher wages, and greater job diversity. However, cost of living (particularly housing) is considerably higher.

Industrial regions: Areas with manufacturing concentrations (Katowice, Łódź industrial zones, automotive production regions) show strong demand for production workers, technicians, and engineers. Foreign worker presence is particularly high in these regions.

Rural and peripheral areas: Some rural and peripheral regions record employment rates 15-20 percentage points below the national average, indicating geographic labour market disparities. These areas face youth emigration, limited job diversity, and economic challenges.

Border regions: Areas near German, Czech, and other Western European borders experience substantial cross-border commuting, with Polish workers pursuing higher wages abroad while residing in Poland. This creates local labour shortages despite geographic proximity to employment.

So what

For candidates: Geographic mobility substantially expands opportunities; major cities offer higher wages and career diversity but higher living costs; consideration of cross-border opportunities in western Poland.

For employers: Regional recruitment strategies must account for vastly different local conditions; organisations outside major centres may need to offer regional allowances, housing support, or target foreign worker recruitment.

Poland has implemented several labour law reforms taking effect in 2025-2026 that affect hiring and employment dynamics:

Pay transparency: Employers must now display salary ranges in job postings, increasing transparency and affecting negotiation dynamics. This reform aims to reduce wage disparities and improve candidate experience.

Remote work recognition: New labour code provisions formally recognise hybrid and remote work arrangements, providing legal framework for flexible work that became common during the pandemic.

Social benefit fund requirements: Companies with over 50 employees must establish welfare funds to support employee well-being, creating additional employer obligations but potentially improving retention.

Minimum wage increases: Scheduled minimum wage increases continue, with the rate rising to PLN 4,666 monthly (approximately USD 1,200) as of January 2025, representing ongoing commitment to raising living standards. This affects approximately 15-20% of workers directly and creates upward pressure on wages more broadly.

These reforms reflect Poland's evolution towards more worker-protective, transparent labour market practices aligned with Western European standards, while maintaining relatively business-friendly overall framework.

So what

For candidates: Increased transparency around compensation improves negotiating position; formal remote work recognition provides legal protections for flexible arrangements.

For employers: Pay transparency requires careful compensation strategy; posted ranges affect both external recruitment and internal equity; compliance with new social benefit requirements creates administrative obligations.

8. Employer challenges intensify: difficulty filling positions

Recent employer surveys indicate that approximately 70% of Polish employers report difficulties finding employees to fill open positions. This represents a structural challenge rather than temporary friction, driven by low unemployment, skills mismatches, demographic pressures, and wage expectations.

Recruitment methods evolving: Employers increasingly use digital recruitment portals (with focus on regional sites), social media, employee referrals, and international recruitment agencies. Traditional public employment services play a role but often insufficient for addressing shortages.

Interviews remain central: Despite digitisation, interviews remain the most important recruitment stage. Employers prioritise cultural fit, practical skills demonstration, and communication ability alongside formal qualifications.

Language considerations: Polish language requirements vary by role. Elementary work (production, warehouse, basic construction) often proceeds with minimal Polish language ability, particularly in workplaces with established foreign worker populations. Professional, customer-facing, and skilled technical roles increasingly require functional Polish, though some technology companies and international firms operate primarily in English.

Expectations gap: Employers often cite applicant expectations (particularly around wages and working conditions) as recruitment barriers. Candidates, particularly younger ones, compare Polish opportunities to Western European alternatives, creating negotiation challenges.

So what

For candidates: Employer difficulty filling positions creates negotiating leverage; demonstrating reliability, practical skills, and cultural fit often matters as much as formal credentials.

For employers: Creative recruitment strategies essential; investing in employer brand, offering competitive total packages (not just wages), and supporting candidate development improves success rates; realistic expectations around language abilities for foreign workers facilitates hiring.

What this means in practice

For job seekers

- Target shortage occupations: Skilled trades, IT, healthcare, machinery operation, and technical roles offer strongest prospects with competitive compensation.

- Develop practical, demonstrable skills: Employers value applied capability; certifications, portfolios, and hands-on experience differentiate candidates.

- Consider foreign opportunities in Poland: For non-Polish candidates, particularly from Ukraine, Asia, and other regions, Poland offers accessible opportunities with established foreign worker communities and employer support systems.

- Pursue technical and vocational training: Vocational qualifications in trades, technical fields, and applied skills address market shortages and command competitive compensation.

- For Polish candidates considering emigration: Evaluate total compensation and career paths; while Western Europe offers higher absolute wages, Poland's lower cost of living, family proximity, and growing opportunities provide compelling alternatives in some cases.

For employers

- Embrace foreign worker recruitment: For logistics, manufacturing, construction, and hospitality sectors, international recruitment is essential; invest in housing support, integration assistance, and multilingual communication.

- Compete beyond wages: Pay transparency and wage pressures require differentiation through development opportunities, clear advancement paths, workplace culture, and benefits.

- Invest in automation and productivity: Labour scarcity requires strategic investments in automation, process improvement, and productivity enhancement to reduce dependence on hard-to-fill positions.

- Build training and development pipelines: Internal skill development, apprenticeships, and upskilling programmes address shortages more sustainably than purely external recruitment.

- Address regional strategies: Warsaw and major city strategies differ fundamentally from smaller city and industrial region approaches; tailor recruitment to local labour market realities.

- Communicate transparently: New pay transparency requirements and candidate expectations demand clear, honest communication about compensation, working conditions, and advancement opportunities.

For training providers and educational institutions

- Align programmes with shortage occupations: Skilled trades, technical fields, IT, healthcare, and machinery operation represent clear sustained demand.

- Emphasise practical, job-ready training: Employers value applied skills over purely theoretical knowledge; hands-on components, internships, and practical projects improve employment outcomes.

- Develop vocational training capacity: Trades shortages require robust vocational education; investment in technical training infrastructure addresses structural gaps.

- Support Polish language training for foreign workers: Language acquisition improves foreign worker integration and expands their employment opportunities beyond elementary roles.

For policymakers

- Address demographic challenges: Retirement age reconsideration, labour force participation incentives for underutilised groups (women 60-64, people with disabilities, rural populations), and family support policies affect long-term labour supply.

- Streamline foreign worker processes: Efficient work permit processing, clear immigration pathways, and integration support directly impact labour shortage resolution.

- Strengthen vocational education: Trades and technical skills shortages require robust apprenticeship and vocational training systems; investment in these pipelines addresses structural gaps.

- Support regional economic development: Policies addressing regional disparities (infrastructure, education, economic diversification in peripheral regions) improve geographic labour market balance.

For all stakeholders

Platforms like Yotru can support these strategies by making skills visible, standardising employer-ready CVs at scale, helping institutions measure learner job readiness, and enabling employers to identify candidates with the right applied experience for Poland's shortage occupations and evolving labour market requirements.

Looking ahead: Structural tightness intensifying through 2030

Poland's 2026 labour market operates with fundamental tightness that will intensify rather than ease through the remainder of the decade. Low unemployment coexists with severe shortages, corporate employment adjustment coexists with unfilled vacancies, and wage moderation coexists with sustained pressure in shortage occupations.

Future performance depends less on cyclical economic conditions and more on how effectively Poland addresses structural challenges:

Demographics: Without sustained immigration at scale, working-age population decline will constrain economic activity. Projected loss of two million working-age people by 2040 creates fundamental labour supply constraints.

Migration dependency: Poland's economic function increasingly depends on foreign workers. Policy frameworks, integration capacity, and geopolitical stability in source countries become critical economic factors.

Skill development: Addressing trades, technical, and healthcare shortages requires substantial investment in vocational training, apprenticeships, and skill development programmes. Current training pipelines insufficient for projected demand.

Wage convergence pressures: As Polish wages gradually converge towards Western European levels (albeit slowly), cost advantages that made Poland attractive for manufacturing and services diminish. Productivity gains become essential for maintaining competitiveness.

Automation and productivity: Labour scarcity and wage pressures drive automation investment. Poland's ability to adopt productivity-enhancing technologies while managing employment transitions determines competitiveness.

Emigration management: Retaining skilled Polish workers (particularly young, educated professionals) requires improving domestic opportunities, working conditions, and career paths to compete with Western European alternatives.

Organisations and individuals who recognise Poland's tight but evolving reality (investing in shortage skills, embracing foreign worker integration, prioritising productivity, and building adaptable skill sets) will navigate the market most successfully. The combination of exceptionally low unemployment, critical skill shortages, migration dependency, and demographic decline creates a labour market where strategic workforce planning and adaptation become fundamental to economic success.